The Bible is quite clear that all of Scripture points to Christ (Luke 24:25-27). Indeed, the purpose of the Bible is to bring people to salvation through faith in Jesus (2 Tim 3:15). But, Paul goes even further than that when he tells the church at Ephesus that all things are being united in Christ (Eph. 1:10). Not just the Scriptures but everything, all creation, is being summed up in Messiah.

Since this is true it should not surprise believers that there will be all kinds of things in creation that “ape” the gospel. There will be cultural items like movies, books, sitcoms, songs, art, literature, etc. that both borrow “gospel themes” and distort them.

Scholars who study this historically usually point to these items and say that the Israelites (or early Christians) picked up these mythological themes in their cultural milieu and built their faith around this common stock of themes. Examples of this would include the flood narrative, the “death and resurrection” of baal as seen in the harvest, the rising of the phoenix, etc. Scholars use these examples to try to disprove the historicity of the biblical story (i.e. the gospel is theology based on story, not history).

I even encountered this argument in college with current popular culture. A student in my freshman English class wrote a paper called, “Why The Matrix Can Replace Christianity,” because of many themes that run through the movie that parallel Christian teachings (there is a post to come on the Matrix). However, these similarities and “borrowings” should not surprise or scare the believer. God designed the universe with Jesus as the goal so similarities to the story of Jesus will be everywhere. Far from disproving the Christian gospel, these themes should bolster our faith as we see the cosmos being summed up in Christ. Also, these Gospel themes give us common ground for apologetic/evangelistic, gospel conversations in the mission fields in which we live because we know this meta-narrative informs their framework for understanding the world, even if in a sinful, depraved and corrupted way.

With this in mind as an introduction I would like to introduce an on-going, occasional series of posts on “The Gospel and Pop Culture.” These posts will be designed to help us think through how to filter movies, music, and other cultural forms through the Gospel matrix. This is something I attempted to do before in the post on Coldplay’s Viva La Vida. What we will do over these posts is offer specific examples, usually from contemporary American culture.

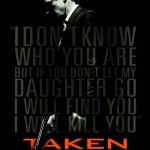

In this post we will examine a movie released in early 2009 called Taken. The basic plot line is a teen age girl goes to Paris without her parents (and against her dad’s better judgment). While there she and the girl she traveled with are abducted by a mob group who traffics in women, and they are going to auction the girls off as prostitutes. It just so happens that her dad is an ex-CIA agent who is skilled in finding and killing bad guys. He tells her captors that he will hunt them down and kill them. He is informed that in these cases typically there is only a 96 hour window to find his daughter before it will become impossible. In the rest of the movie her dad tries to track her down, rescue her and make her captors pay. Her dad takes bullets, goes without sleep, and risks his life all in hopes of finding his daughter.

In this post we will examine a movie released in early 2009 called Taken. The basic plot line is a teen age girl goes to Paris without her parents (and against her dad’s better judgment). While there she and the girl she traveled with are abducted by a mob group who traffics in women, and they are going to auction the girls off as prostitutes. It just so happens that her dad is an ex-CIA agent who is skilled in finding and killing bad guys. He tells her captors that he will hunt them down and kill them. He is informed that in these cases typically there is only a 96 hour window to find his daughter before it will become impossible. In the rest of the movie her dad tries to track her down, rescue her and make her captors pay. Her dad takes bullets, goes without sleep, and risks his life all in hopes of finding his daughter.

There are several “Gospel themes” in Taken. An overview of the gospel storyline of the OT is that God’s wayward son, Israel, is “taken” captive and brought into a foreign land because of his sins and foolishness (in the movie the daughter lies to her dad about what she will be doing in Paris, and her friend makes dumb, immature decisions that lead to their abduction). God promises to rescue His people (His son) from the place that they have been “taken” to, to destroy their captors, and to bring them back to their home. Taken follows the same plotline. Jesus’ ministry in the NT is presented as the fulfillment of this promise. The Gospel story is that God through Jesus rescues his people from captivity (cf. Rom. 6), reverses their exile (Heb. 10:19-22), and will destroy the enemies. After all, He is the “Good Shepherd” who seeks out and rescues the “lost sheep” (cf. Ezek. 34; John 10). Jesus is the Son of Man who will destroy the beasts, judge the nations, and vindicate His people (cf. Dan. 7). He is the Messiah of Psalm 2 who dashes his enemies with a rod of iron (cf. Isa. 11; Rev. 12). He is the Revelation 19 Warrior who finally avenges the blood of his people and feeds their enemies to the birds. He is the one on the mission of the Father to run toward and restore the “lost son” (Lk. 15).

There is another theme from Taken. In Rambo-like fashion Liam Neeson’s character seems to take on an entire army himself. One man is the rescuer and warrior. This is a gospel theme that starts as early as Samson. In Judges God begins rescuing his wayward people through judges who lead armies. But with Samson, He shows that He can rescue through 1 man, even taking on thousands of Philistines. Then there is David, again a solo champion, who takes on a seemingly impossible task, defeating the Giant and rescuing his people. This climaxes in Jesus who is the solo champion who rescues the world and defeats the ultimate enemies! The theme of one man against the world to rescue his people did not start with Rambo.

These themes that mirror the gospel are in Taken, but they merely ape the true gospel and are an inferior, even twisted version. The hero of Taken is deeply sinful in that he chose his job over his family. Unlike the hero of the true gospel story Neeson’s character is trying to atone for his own past sins, whereas Jesus atoned for the sins of others. Neeson abandoned his covenant to his bride (and child) whereas Jesus died in covenant love and commitment to his bride. That is just one example among many. Still, there are gospel themes running throughout the story.

So what? Do these parallels really matter? Here are a few reasons why it matters. First, we need to be able to deconstruct the messages being preached to us through media both for our own families and the people we minister to.

Second, the Gospel meta-narrative that all things are being summed up in Christ explains the deepest longings of the human heart. This can be used in sharing the Gospel with the lost of any culture. The church must identify the “Gospel themes” that resonate in their specific culture and context, and then use these themes to proclaim the Gospel. Some themes, like in this movie, will cross all cultures. The Gospel alone, not genetic makeup or evolutionary theory, explains why a parent’s love can be so strong and sacrificial (cf. Matt. 7:11). The Gospel alone explains why abusive fathers are so devastating, and it explains why little girls long for a daddy who will be there for them in a protective and loving way. These things are not “just the way it is.” There is a reason for these human longings. God designed the world with Jesus in mind. These longings point us to the gospel and God’s fatherly, rescuing love for his children (especially His “only begotten Son” who was also “taken” captive, “exiled” from God’s presence, murdered and rescued on the 3rd day).

Third, in regards to this movie specifically, we have lost in contemporary evangelicalism the theme of Jesus as Warrior-hero. Jesus is seen as guru, hippie, and a boyfriend we sing love songs to. That is a reason why the church in large part is devoid of male leadership, and we are failing at reaching men. Men resonate with characters like Jack Bauer and Liam Neeson’s who are violent rescuers. They resonate with a man who is a hero and can get the job done. This resonation is because God designed the world with Jesus, the Warrior-King, in mind.

The joy in our hearts at watching a man go after his captured and tortured daughter, a man who refuses to be stopped by bullets ripping into his flesh, reveals the longing within us for a Warrior who will against all evil rescue us from our enemies and give us rest. This longing is not conjured up by mere cinematic drama. The longings of our hearts are summed up in the words of the daughter in Taken when she finally sees her dad, “Daddy, you came for me?!” This longing will only find satisfaction when we see a Galilean riding on a white horse with robe dipped in blood and sword in hand who promised us “I will come for you” (John 14).

-Jon Akin